Digital performance

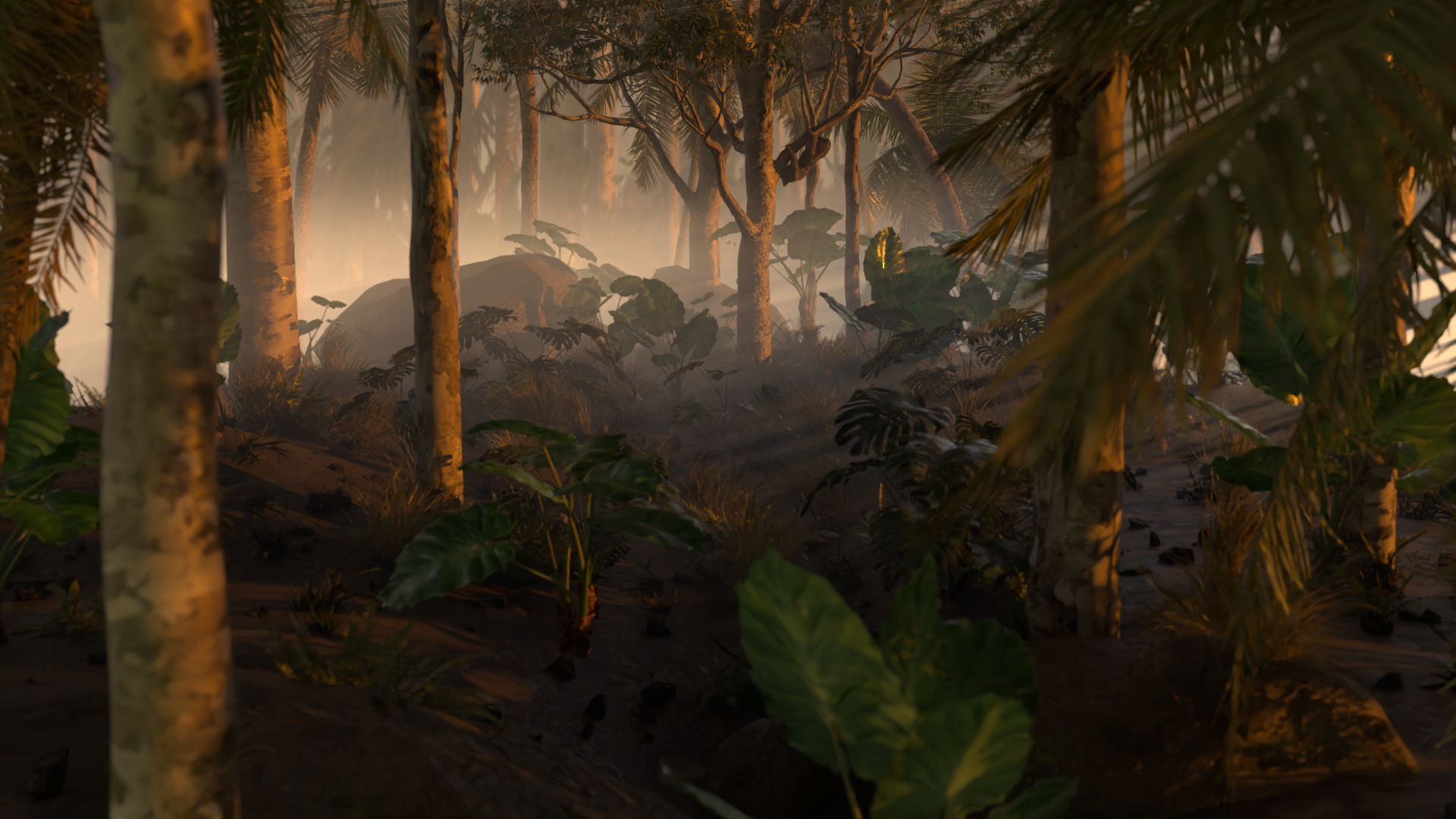

The sloth spends a significant portion of its life in the treetops, hanging from branches and moving at an incredibly slow pace. This passive lifestyle inadvertently leads humans to associate sloths with laziness, incompetence, and clumsiness. However, its slow movements are actually a significant evolutionary advantage. Just as some animals have adapted by increasing their speed to escape predators, the sloth’s life has progressively slowed down, allowing it to simply vanish from predators’ sight.

Due to its lifestyle, various species of moss, fungi, insects, and molds can grow or survive on the sloth, further enhancing its chances of successful camouflage. In a sense, the sloth goes against the grain. Instead of constantly accelerating, the sloth slows down, sleeps more, consumes less food, and excretes less. The act of excretion is one of the most mysterious activities observed in the life of a sloth. It can perform most of its activities in the treetops, but once every seven days, the sloth descends to defecate. These are the most vulnerable moments of its life, and there is nothing to protect it from becoming easy prey. Most sloths killed by predators die during the act of defecation.

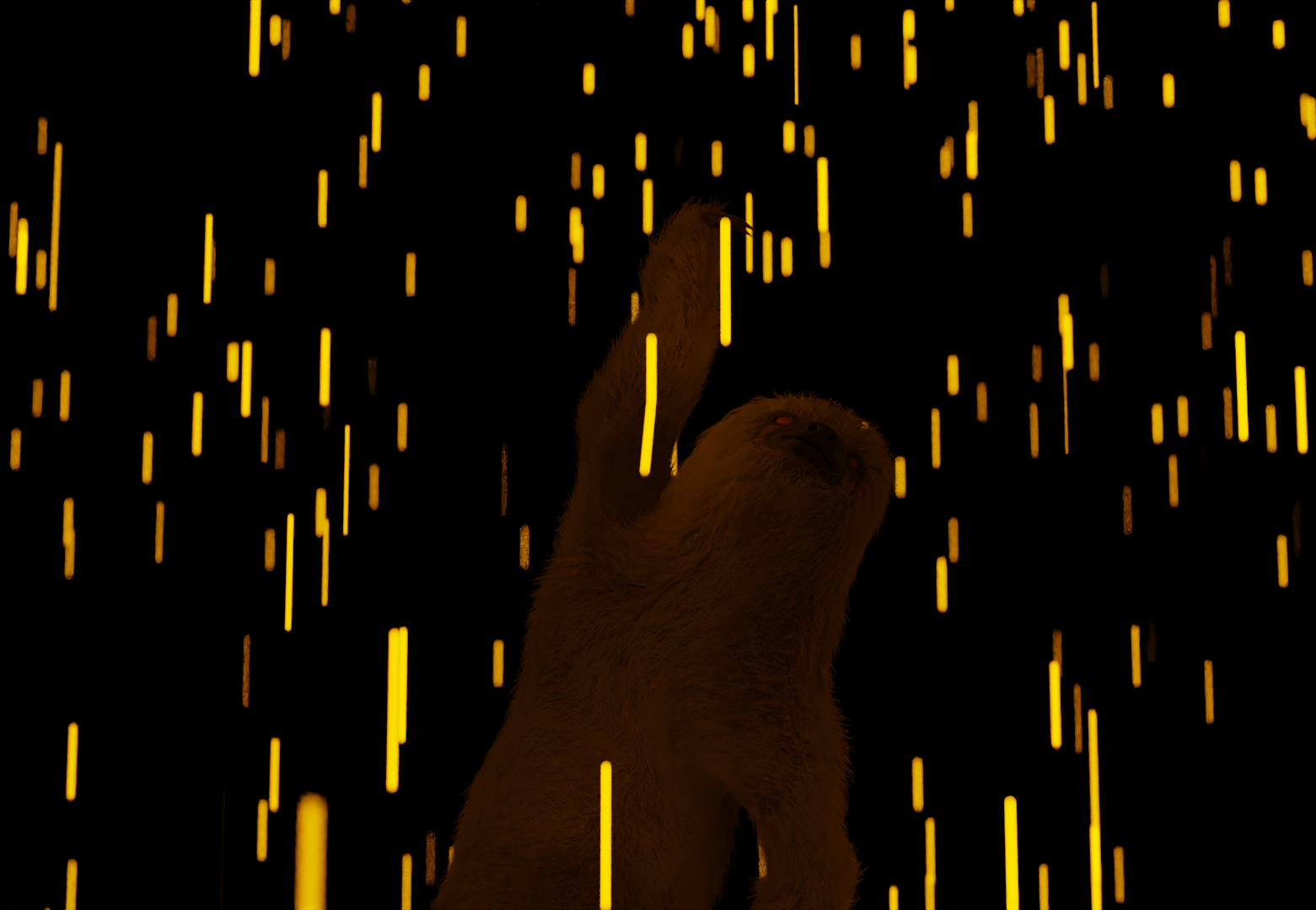

This mysterious activity has no clear evolutionary justification. However, if it were not vital for sloths, this behavior would have vanished along with the individuals practicing it. Sloths exclusively defecate at the base of trees. One intriguing explanation is that many insect species living in its fur require the sloth’s excrement for reproduction. Some can lay eggs only when in close proximity to the excrement, which can only occur when the sloth descends from the branches. A contributing factor to this peculiar situation is that to date, we have found four insect species that live nowhere else but in sloth fur.

What a strange relationship. An animal seen as so incapable and slow in the eyes of humans is suddenly directly responsible for four additional animal species. How many more would we count if we considered those indirectly dependent on the sloth? This raises the question: How many dependent species would we count if we looked at an aggressive and expansive species like humans?

The sloth’s fur is an entire universe for some species. Once every seven days, the sloth risks its life to save not just one other individual or even four other individuals, but at least four other species.

The sloth spends a significant portion of its life in the treetops, hanging from branches and moving at an incredibly slow pace. This passive lifestyle inadvertently leads humans to associate sloths with laziness, incompetence, and clumsiness. However, its slow movements are actually a significant evolutionary advantage. Just as some animals have adapted by increasing their speed to escape predators, the sloth’s life has progressively slowed down, allowing it to simply vanish from predators’ sight.

Due to its lifestyle, various species of moss, fungi, insects, and molds can grow or survive on the sloth, further enhancing its chances of successful camouflage. In a sense, the sloth goes against the grain. Instead of constantly accelerating, the sloth slows down, sleeps more, consumes less food, and excretes less. The act of excretion is one of the most mysterious activities observed in the life of a sloth. It can perform most of its activities in the treetops, but once every seven days, the sloth descends to defecate. These are the most vulnerable moments of its life, and there is nothing to protect it from becoming easy prey. Most sloths killed by predators die during the act of defecation.

This mysterious activity has no clear evolutionary justification. However, if it were not vital for sloths, this behavior would have vanished along with the individuals practicing it. Sloths exclusively defecate at the base of trees. One intriguing explanation is that many insect species living in its fur require the sloth’s excrement for reproduction. Some can lay eggs only when in close proximity to the excrement, which can only occur when the sloth descends from the branches. A contributing factor to this peculiar situation is that to date, we have found four insect species that live nowhere else but in sloth fur.

What a strange relationship. An animal seen as so incapable and slow in the eyes of humans is suddenly directly responsible for four additional animal species. How many more would we count if we considered those indirectly dependent on the sloth? This raises the question: How many dependent species would we count if we looked at an aggressive and expansive species like humans?

The sloth’s fur is an entire universe for some species. Once every seven days, the sloth risks its life to save not just one other individual or even four other individuals, but at least four other species.